About Jean: African-American Writing a New Middle Grade Novel

Jean Perry

What: As a reporter for the New York Daily News, I went to interview the wife of an African diplomat.

Leaving the couple’s Upper East Side apartment, I saw a girl, who appeared to be a young teen, sitting in the kitchen. A human trafficking case, involving two domestic servants from the Philippines, had only recently been in the news, and I wondered if the girl I saw might be a victim. She looked young and I wondered why, it being a weekday, she wasn’t in school. Walking back to the News’ headquarters, then on east 42nd Street, the pros and cons of telling my editor what I saw tumbled before me. First I was shocked that there was such a struggle. I’d seen something that didn’t sit right with me. Report it. That should have been a no brainer, except it wasn’t.

In my mind’s eyes, a spectacular drama, complete with actors, moving pictures and sound, arose in front of me. As scene after scene appeared, I saw myself in imagined scenarios.

It’s my experience that fear uses imagination. It is a fertilizer for all the little seeds implanted in me from life: parents, friends, neighbors, school, church, and media. All the seeds that shout out you can’t, therefore, don’t try. I’ve found that fear will grow these seeds into full-blown, terrifying images that pop up before me appearing to be in real-time, although they are only images of my own creation.

These falsehoods play all kinds of tricks on me. Paralyze me and toss before me the most way-out, weird, outlandish, images of bad things that may happen, as the result of an action I take—before I take the action. Why so much drama when it’s just going to the authorities making a report. But no. I watched, in my mind’s eye the worst scenarios: perhaps I’d be assaulted for sticking my nose into a diplomat’s business. Or laughed at when it turned out that the girl was eighteen and a paid employee. I didn’t realize it then, but my only concern was about me, not at all about the girl.

Only years later would I learn what force was behind that script. I felt like a mouse batted back and forth by a cat. Report and help the girl or stay quiet and safe. What was I afraid of?

I was afraid of being wrong. No matter that a person was possibly being inappropriately and illegally used as a domestic servant. I, my ego, could not risk being wrong. So I did nothing. Yet I returned to my office saying nothing about what I’d seen to my editors. Nor did I report my suspicions to the authorities. I was a coward. By not having the confidence to go forward I was fully in the grip of Ego.

The image of the barefoot girl haunted me for years. Fear kept me silent. Illogical, inappropriate misplaced fear kept me frozen when walking into an FBI office might have triggered an investigation into what I’d glimpsed.

If what I’d seen turned out to be nothing—the “girl” perhaps was actually over eighteen and legally employed, then no harm done, I’d done my job as another human being, and shown concern for another being’s welfare. But if an investigation turned out to show a valid case of trafficking, I would have saved a life. I’ll never know. One thing I do know is that when it’s your turn, speak, or be as haunted as I am by what you didn’t do. Had I reported my suspicions to the authorities, at least a report would have been written. Perhaps an investigation would have taken place.

When and Where: Born in Harlem in New York City I grew up watching Alan Freed and American Bandstand, in a gang-free, drug-free, two-parent home environment.

My parents, part of the wave of black Americans migrating from the South to the East Coast, were serious about education and work.

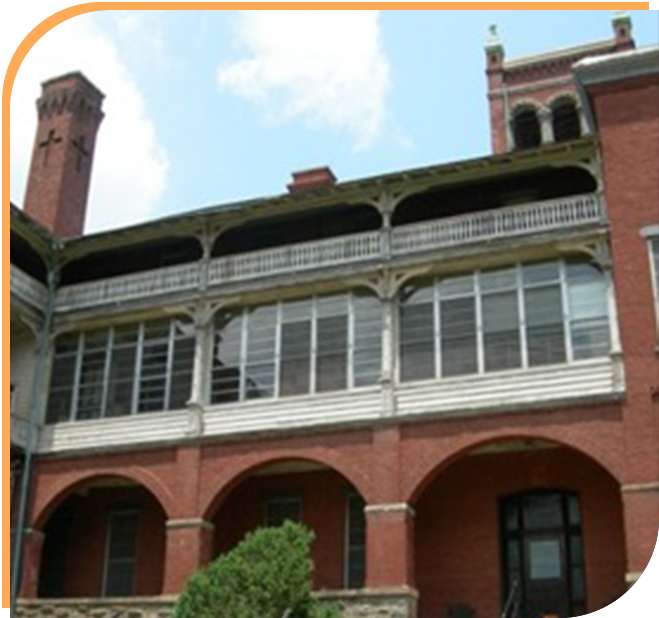

At age nine I began therapy at the Northside Center for Child Development, then housed in the Rhodes School on Central Park North. This was the clinic founded by world-famous black psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clarke. In pre-drugs Harlem I could walk around safely and travel on city buses unescorted.

During one session, I became convinced that my therapist was more interested in studying me than helping me because with me sitting across the desk from him, he piled both of his feet on the table so that the soles of his shoes (large) were directly in my face. That did it! Thinking back, he may have wanted to see if I could protest this gesture and speak up for myself. I could have but didn’t say: ‘Hey, get your feet out of my face.” Or more my style, ‘Doctor F would you take your feet down, they’re bothering me,’ though both would have been a tall order for a nine-year-old. At any rate, I decided to find a kindly ear elsewhere.

Most days after school I took the bus from PS 192 to the George Bruce Branch of the New York Library at 581 West 125th Street at Amsterdam Avenue where I read what I wanted, did homework in the gloriously huge children’s room, then got on the bus again and went home.

Other days, especially if there was Story Hour, I’d leave school and go to a library closer to my house, the Harlem Branch at 9 West 124th Street.

One early evening, I noticed the Handmaids of Mary convent next door. Hm-m-m maybe someone there would listen and listen with love. This opened a lifelong friendship with Sister Miriam Cecelia.

In 1960, I entered a convent boarding school: St. Francis de Sales, in Powhatan, Virginia. At the end of my freshman year decided not to return because I wasn’t allowed to read a book on the juniors’ reading list. Graduated-Julia Richman, High School, Manhattan.

After working a couple of years I went to the Fashion Institute of Technology earning an Associate’s degree with a major in Fashion Communications. I transferred my credits to New York University, majoring in journalism and receiving a Bachelor of Science degree. From there I became an editorial trainee at the New York Daily News and was hired as a general assignment reporter nine months later. I worked in the police, criminal courts, rewrite, fashion, and health and fitness. After thirteen years I left the News and returned to school for an Associate’s degree in Hotel and Restaurant Management. Completing an internship at the Greenbrier Hotel in West Virginia.

While working in the restaurant business I became Health and Fitness Editor of Essence Magazine. After eighteen months there, I returned to school, earning a Master of Arts degree in curriculum and teaching from Columbia University, Teachers College.

I was an assistant teacher at Ethical Culture School, Manhattan for two years before moving to Los Angeles. In LA I taught elementary school for for twenty-five years with the Los Angeles Unified School District, and I have been a Free-lance writer for the Los Angeles Sentinel, contributing stories to the Los Angeles Times. I have traveled to Africa, Europe, Mexico, and the Caribbean.

READ THE LATEST FROM JEAN’S DESK!